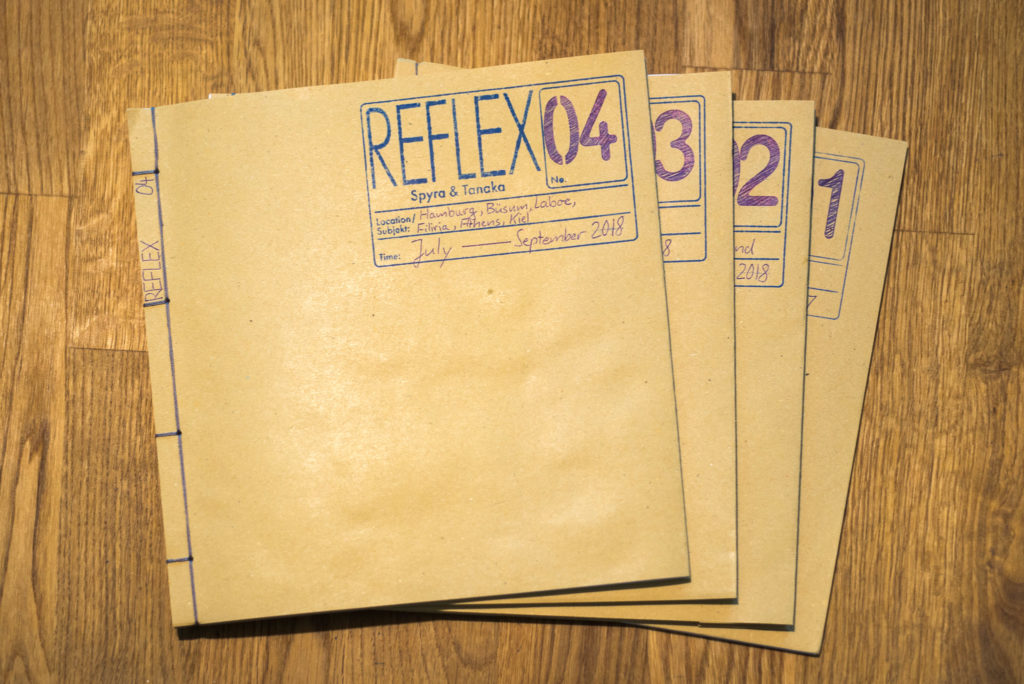

Reflex issues 01 to 04 are finally finished. Each issue contains 36 of my photos taken during one quarter year, printed using electro photographical printing.

It’s been a long time coming: In March of 2018 I wrote that I would concentrate on printing my photos, instead of just publishing them on my homepage. Afterwards it seemed like no progress happened in this regard for well over one year. What can I say? The PhD thesis continues to occupy the largest part of my attention and from last summer onward, curating the exhibition “Negative/Scans” kept me busy as well. As a result, the stream of photos published on the homepage became a mere trickle, while no printed photos appeared.

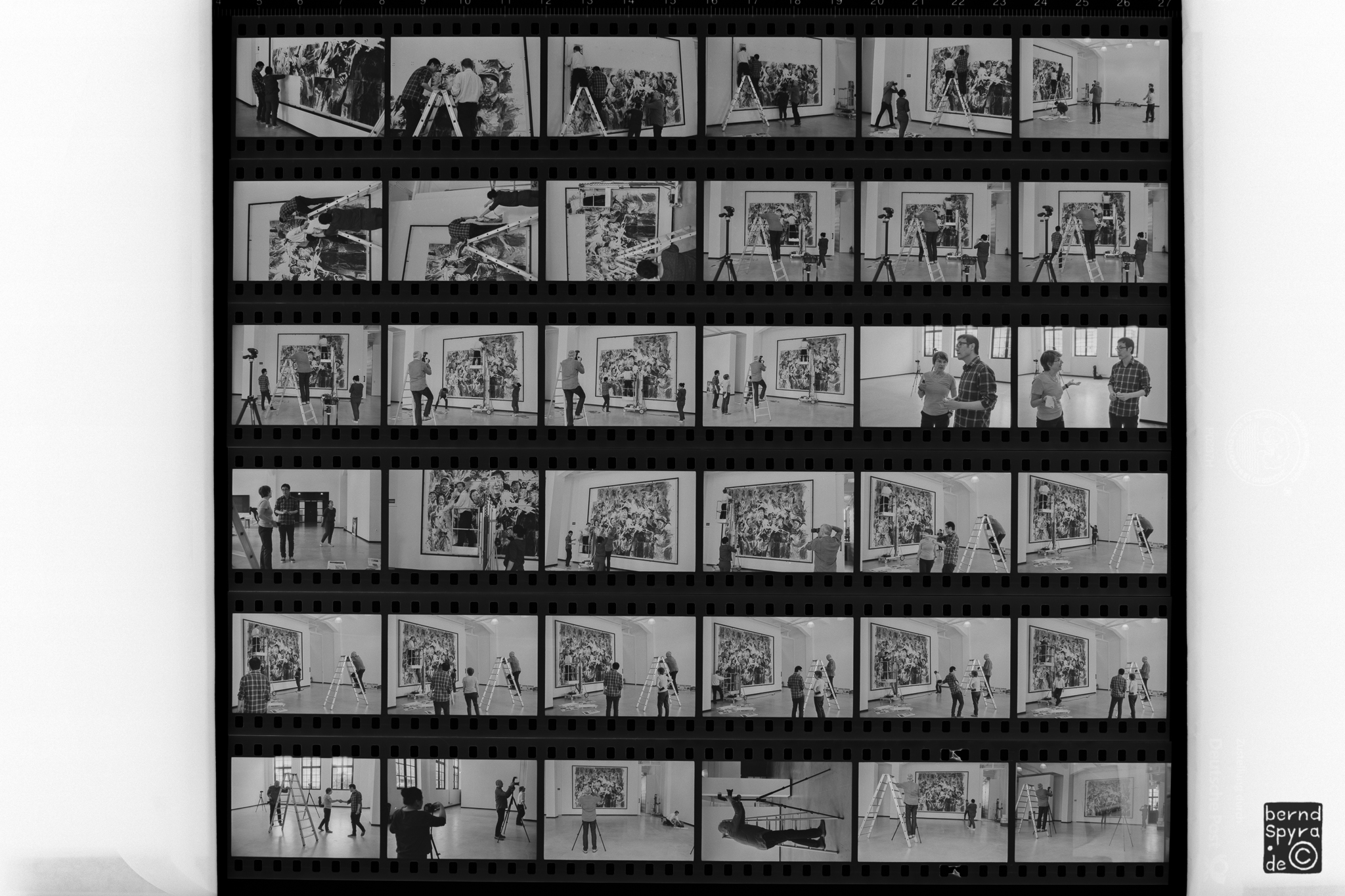

I continued shooting though, as well as developing films and making proof sheets of the films. When some time was available, I experimented with different ways to print my photos.

The question of printing process

The major reason why the silver bullet – traditional enlargements, chemical development – could not be used: Our apartment lacks the space necessary to set up a darkroom able to handle print development. Turning the bathroom into a darkroom by putting an enlarger onto the toilet seat and some development trays in the shower is nice for some fooling around, but not for producing a reasonable quantity of prints. The throughput rate would be far too low. While I do hope to be able to set up a real darkroom again in the future, for now I will continue to use a hybrid workflow, meaning I take my photos on film, scan them and use the computer to prepare them for printing.

Besides the question of the throughput – or maybe better output – rate, there were further requirements which the printing process would have to meet:

– The prints need to be reasonably archivable (they should not degrade before I do, print durability should be in excess of 60 years)

– The prints should cost as little as possible (a drugstore print of the size 13x18cm costs around 0,40€. Nice for a few quick prints, but too much when having to print a lot)

– Print quality (resolution, tonality, luster) should still be as high as possible

After some experiments with on-demand digital photobook printing, which proved to not be right for me due to reasons of cost and lack of control over the process, I tried to print the photos myself using an inkjet printer. That one did a good job preserving the tonality of the negatives, but I do not print every day (or even week) and the danger of inks drying out in the printer is looming too large. (The printer wasting ink on purpose to flush out its printing heads is also unacceptable for financial reasons.)

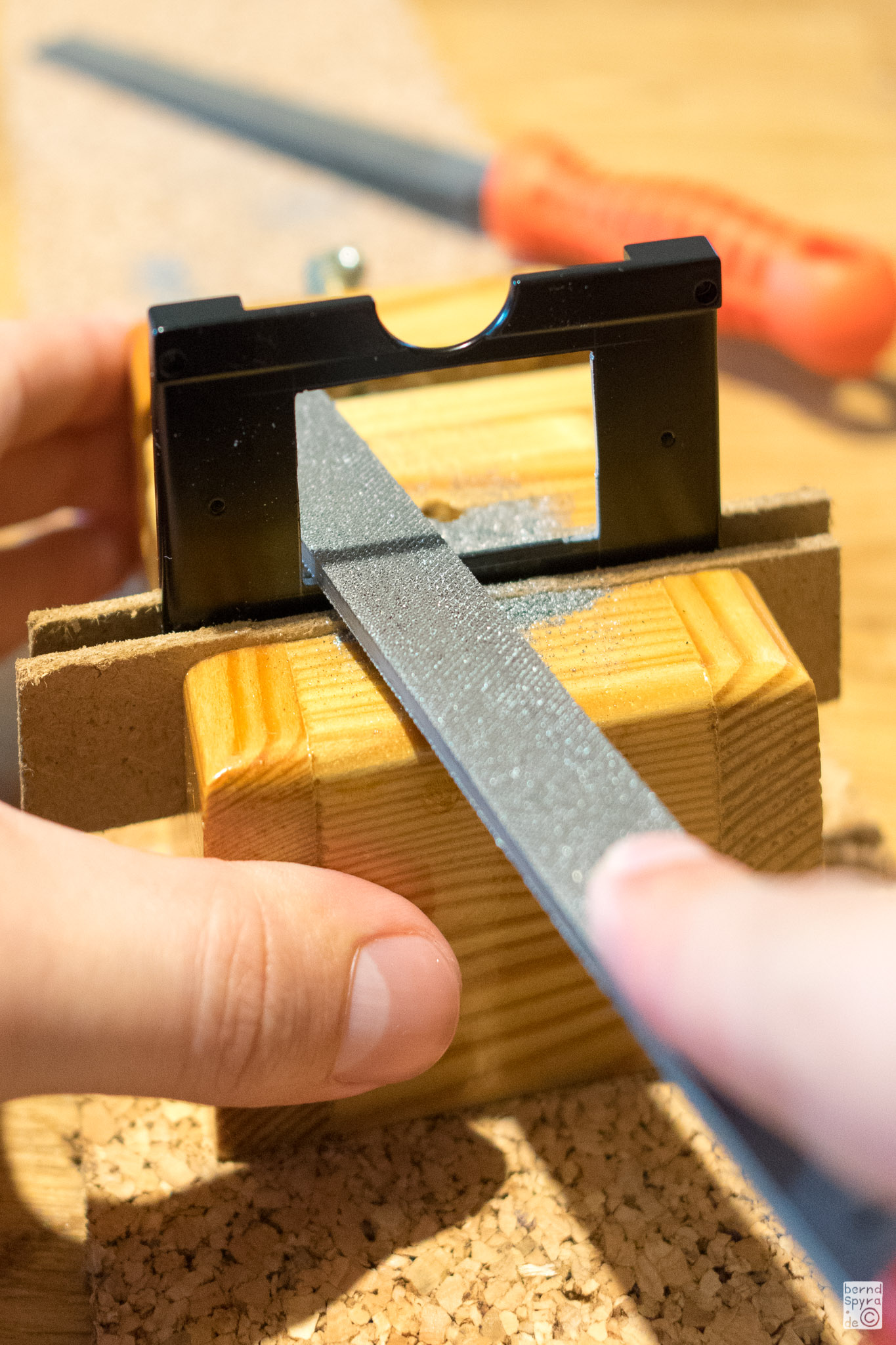

I then stumbled upon “xerography” or electro photographical printing. The prints meet common archival standards and are not very costly in production. Their only downside is that tonality is not too good (resolution is reasonable though). Even if electro photographical printing sounds exotic to you, you probably have already encountered the process: It is the same one used in the humble photocopier. Following some deliberations, I figured since exhibition prints would be done through a different process anyway, xerography is the way to go for producing this little ongoing catalog of my work.

The editorial workflow for “reflex”

After the question of printing process was settled, another decision had to be made on how to edit my photos. Sometimes I work on limited projects, which turn into little portfolios of photos almost by themselves (compare the Greek wedding), but what about the photos I take day-to-day without any connecting thread? These form the bulk of photos I shoot, by a wide margin.

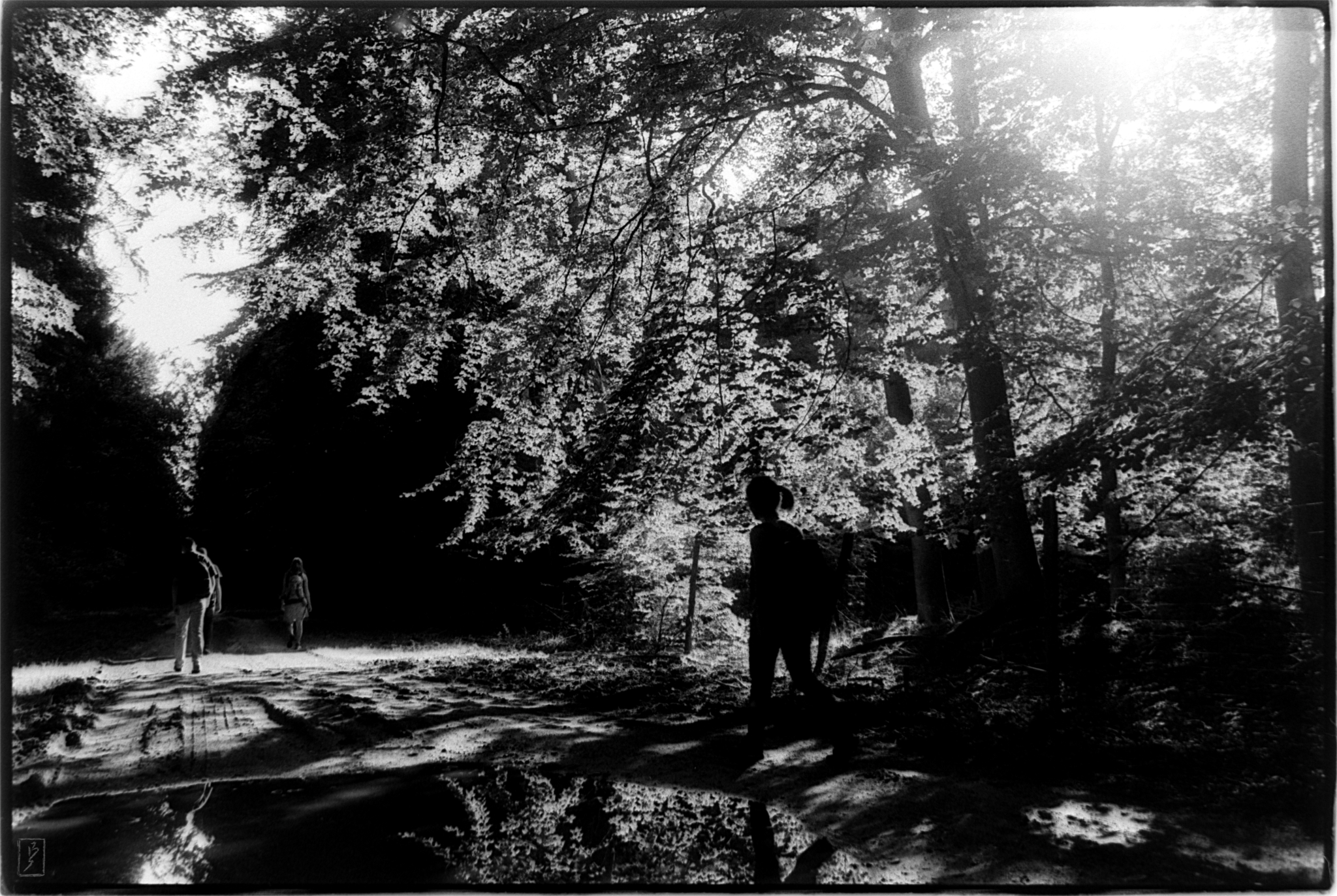

I decided to select 36 out of all the photos I take every quarter year (Jan.-Mar., Apr.-Jun., Jul.-Sept., Oct.-Dec.), purely based on the criterion of which photos I like. These will be printed, presented and archived together. What results over time will be a kind of photographic reflection of the world around me, in the shape of a photographic journal. The focus is smack on the pictures, usually printed one per page with as little captions provided as possible.

My wife Shoko helps me to embed the 36 photos selected into a simple layout using the software InDesign. After printing the pages, I stitch them together between two sheets of packaging paper, resulting in a durable booklet of 21cmx21cm. On the front of this, the most important information about the content is given, as well as the issue’s number.

Let’s see how long I can keep this up.